Ticket Viewer

-

23 July 2017 |

-

28 July 2017 |

Another month, another interesting coding exercise. I haven’t posted much in here lately. The reason is I’ve been working on a fairly large Rails app and haven’t had time, nor brought it to a sufficient state of completion to be worth showing off.

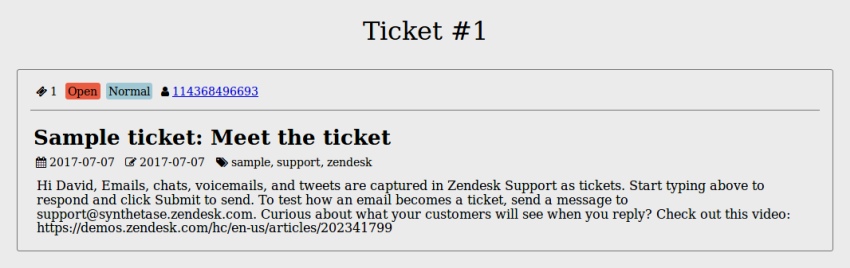

In the middle of this, I was set a coding challenge by Zendesk, a company I applied at, and found a use for my new Rails knowledge. The requirements were to build an app to hit the company API and download support tickets. The tickets must then be displayed to the user, with no more than twenty-five per page. The user must also be able to obtain useful information from the ticket. It’s a fairly simple task, with no requirement to actually manipulate the tickets, just display them.

The external ticket API blocks all cross-origin requests, so getting ticket data using a JS front-end framework was out of the question. Since I now have some experience using Rails, I opted for that instead - although I admit a lighter framework would arguably be more appropriate.

Writing the app

The main component of the app was a wrapper for the API. I created a module with getter methods that send GET requests to the service for ticket data. Although not part of the requirements for the challenge, you could easily extend this module and add setter methods which send POST requests to add tickets as well.

The getter methods accept an optional hash containing query options which are supported by the external API. This makes it very easy to change the behaviour of the app by simply altering the query parameters. The API supports pagination, so I just used this to satisfy the twenty-five per page part of the requirements.

ZendeskAPI.get_tickets(per_page: 25, page: 2, sort_by: :created_at)

#the query params are easily dealt with:

query_string = '?' + query_hash.map { |k,v| "#{k}=#{v}" }.join('&')

The wrapper module also defines a Response class for dealing with the API responses. This class handles any errors the API might return and logs them both to file and the console. It also allows the controller to know about errors via a simple #error? method.

If there are no errors, the class stuffs the response data into an instance variable, which allows the controller to access it for rendering the tickets on the page.

The rest of the app is pretty straight forward: the controller handles the requests and calls the appropriate getter methods on the API wrapper module, then renders the results on the page. If the API returns an error code, an error message is displayed to the user instead.

Testing the app

This is where the real fun begins ;)

In my limited experience with Rails, I haven’t done much in the way of testing (I know, I’m a very bad boy…) so it was about time I did some in earnest. I found fairly quickly that I didn’t really like the Rails testing framework as much as rspec, so I removed it and added rspec to the Gemfile instead.

The fun part was having to mock all the external API calls so the tests didn’t actually hit the end-point when running. This is a good idea for several reasons:

- It significantly improves the speed of the test suite because you don’t sit around waiting for the API to respond.

- It allows you to run the tests even if the API is unavailable (or if you’re only allowed a limited number of requests per day and you don’t want to waste them on testing).

- It allows you to write tests for code that hits APIs that haven’t been written yet.

- Lastly, (and I think this is probably one of the most important points from a software engineering philosophical standpoint) we aren’t testing the API, we’re testing our own code, so actually hitting the API and checking its responses is outside the scope of the test suite.

If you know the API spec, you know how it will respond to any given request and you can write a mock response for your test suite. To do this I used a gem called Webmock which makes the whole process ridiculously easy. You can set it so that under a test environment, no external HTTP requests are permitted. Then, if it catches a request, it throws an error to the console telling you exactly what the request was and how to write a mock response for it. Too easy.

Just putting up a mock fascade is one thing, but what happens when your program wants to actually do something with the data it thinks is being returned? Since you’re not hitting the external API, you can hardly expect it to give you lots of delicous JSON in response, so what to do? The Factory_Girl gem is your friend here. You can use it to instantiate a series of mock objects, so that your code has something to play with.

In my case, I created a Ticket factory that produced a Ticket object for a single ticket request. Then I simply asked for an array of Tickets if the request was for a page listing of tickets. I wrapped the call to Factory_Girl in a MockResponse module and called the module methods in my Webmock response stubs.

For end-to-end testing, I used Capybara. Usage is quite intuitive and it was easy to tell it to visit a particular page in the app to verify that it had the elements I expected to see or lacked those that should not have been present.

Conclusions

I learned a lot about getting a decent test suite up and running in Rails during this exercise. I also learned the value of a good test suite while developing. It was really nice to be able to do a bit of re-factoring and them simply run the suite to verify that everything still worked as expected. I definitely think that spending a bit of time learning this will save me a lot of headaches in the future! :)